- Modernist period began 1750's when large scale capitalism,industrialisation and urbanisation was introduced to europe.

- GD in the 20's was a rejection of the ornamental art forms. GD was free from popular trends and fashion.

- Was form follows function.

- For example San Serif typefaces.

- This gave further clarity within communication.

- Modernist design included factors such as: clarity, Legibility, Good visual communication and no barriers in nationality and culture.

- toulouse- letrec one of the founders of modernist GD.

- he created a blurred distinction between art and design.

- the depiction of modern life through design.

- Mannetti "zang tumb tumb" a poem created in a modernist and creative way. through the manipulation of type.

- Futurist Design

- Fortunato Depro (1927) Modernist book binding.

- No fonts were used with the exception of san serifed bar grokests.

- Swiss were the forward thinkers in GD post WW1- Helvetica.

- Photography and photomontage prevalent with in design.

Thursday, 30 December 2010

Graphic Design and Modernism in Brief.

Revolutionary Design in Russia.

- Europe always considered to be the heart of modernity and industrialisation

- between 1917-1925 revolutionary design took place largely due to social change and radical advances in artistic reflection.

- Nov 7th 1917 Bolsevihks ( armed revolutionary workers).

- Lead by Lenin in St Petersburg. Attacked the government.

- Tzara over thrown workers seize control of state.

- lenin controls russia- communist government

- USSR 1917-1989

- Ruled by people

- not complete equality

- 'october' directed by Sergei Einstein 1927.

- Celebrates 10 years of revolution. related to previous ideas that the king was put there by God.Modernism attacks this idea and replaces it with more scientific ideologies.

- Pre progression ( imagery)

- Expressionism in modernity

- 60% of Russian illiterate

- Images clear and symbolic due to this illiteracy.

- Red symbol of communism and russia.

- Colour chosen by Bolshevihks

- symbol of the blood of the workers.

- 1917-1920's intense artistic expressionism.

- Lenin dies late 1920's

- Stalin takes over and this symbolises a change in art and design, progression in halted.

- Stalin-totalatrianism

- destroys expressionism

- progressive art not approved by Stalin.

- Art became very expressionate and modern

- art still very symbolic communicating to the illiterate masses

- Rodchenko was commissioned in a utilitarian project to promote public libraries and book stores.

- Red font in this piece is symbolic of Bolsevihks.

- Photographic imagery modern(revolutionary)

- Franz Ferdinand mimicked Bolsevihks

- Print Became popular (cheap,easy)

- construction of a new society-exhibition

- different disciplines working together

- Tatlins model of the movement of the third international

- Created as a demonstartion of russian deveopment and forward thinking

- Vketemas russian progressive art school

- pre dates bauhaus

- opened to train interdisciplinary constructivist design.

- Vkutemas closed by stalin (to radical)

- Revolution=new opportunity to art progress

- Constructivist, desire to make art useful

- Art a chance to construct a new society

- by the end of the 1920's artistic freedom non existent

- 1934 Stalin decrees social realism only.

Modernity and Modernism

Modernity- The quality or state of being modern."a shopping mall would instill a spirit of modernity into this village".

Fresh,new,contemporary.

Modernism-Modernism, also known as the Modern Movement, marked a conscious break with the past and has been one of the dominant expressions of design practice, production, and theory in the 20th century and is generally characterized visually by the use of modern materials such as tubular steel and glass, the manipulation of abstract forms, space and light, and a restrained palette, dominated by white, off-white, grey, and black. Following on from the well-known phrase ‘Ornament and Crime’ coined by Adolf Loos as the title of an article of 1908, later echoed by Le Corbusier in his assertion that ‘trash is always abundantly decorated’, was the notion that the surfaces were generally plain. When decoration was used it was restrained and attuned to the abstract aesthetic principles of the artistic avant-garde such as those associated with De Stijl orConstructivism. Also closely associated with Modernism was the maxim ‘form follows function’ although in reality this was often more symbolic than the case in reality, a visual metaphor for the Zeitgeist or spirit of the age. Nonetheless Modernism found forms of material expression alongside exciting, new, and rapidly evolving forms of transport and communication, fresh modes of production and materials coupled to technological and scientific change, alongside a contemporary lifestyle powered by electricity.

The roots of Modernism lie in the design reform movement of the 19th century and were nurtured in Germany in the years leading up to the First World War. The Modernist legacy is considerable in terms of design (whether furniture, tableware, textiles, lighting, advertising, and typography or other everyday things), architecture (whether public or private housing, cinemas, office blocks, and corporate headquarters), or writings (theories, manifestos, books, periodicals, and criticism). This has done much to cement Modernism firmly into the mainstream history of design. Furthermore, it is also heavily represented in numerous museums around the world that have centred their design collections drawn from the later 19th century through to the last quarter of the 20th century around the Modernist aesthetic and its immediate antecedents. This focused collecting policy has generally been at the expense of the representation of many other aspects of design consumed by the majority in the same period. Typifying such an outlook has been the Museum of Modern Art in New York, established in 1929. The curatorial inclinations of Philip Johnson, Eliot Noyes, and Edgar Kaufmann Jr. dominated its collecting policy for several decades. A further significant reason for the prominence of Modernism in accounts of design in the 1920s and, more particularly, the 1930s has been the fact that it was underpinned by social utopian ideals and identified with radical avant-garde tendencies opposed to the repressive political and aesthetic agendas of totalitarian regimes that dominated in Germany, Russia, and Italy. In general, official architecture and design practice under Adolf Hitler and Josef Stalin favoured an authoritarian, stripped down neoclassical style, leading many progressive designers in Germany in particular to emigrate in the face of restricted professional opportunities and increasing political and social oppression. In dictator Benito Mussolini's Fascist Italy, the position was slightly more ambivalent during the 1920s but the Modernist aspirations of those associated with Italian Rationalism found little official patronage in the interwar years. To many eyes in 1930s Britain Modernism was also felt to reflect ‘Bolshevik’ tendencies and was out of tune with the more historically inclined stylistic rhetoric of British imperialism (see British Empire Exhibition), an outlook that oriented Britain away from continental Europe towards the dominions and colonies of Empire. Known also as the International Style from the late 1920s onwards, a later phase of Modernism was also, by its very definition and aspiration, opposed to the strongly nationalistic tendencies in many countries in the turbulent political and economic climate of the 1930s. Less affected by the political turmoil in the rest of Europe were Holland and Scandinavia where Modernism found considerable opportunities for further development and dissemination. After the Second World War the International Style was taken up by many major multinational companies for the architecture, interiors, furniture, and furnishings and equipment of their offices and showrooms, thus promoting themselves through their emphatically modern identity as efficient, up-to-date, and internationally significant organizations in a global economy. In the eyes of some, Modernism's earlier associations with social democratic ideals had been transmuted in its later manifestations to support capitalist ends. Used widely in design and architecture in the 1950s and 1960s, such stylistic traits also attracted increasing criticism from a younger generation of designers, architects, and critics who felt that an abstract design vocabulary that had evolved in the early decades of the 20th century was no longer relevant in an era of rapid and dynamic change, of television and radically developing media and communication systems, and of swiftly developing opportunities for mass travel and the direct experience of other cultures. Such trends found expression in the increasingly rich and vibrant vocabulary of Postmodernism, echoed in the increasingly ephemeral lifestyle enjoyed by those in the industrial world with greater levels of disposable income. Ideas about what was called ‘Good Design’ in the 1950s and 1960s were formally linked to the Modernist aesthetic but without the social utopian underpinning promoted by many of the first generation of Modernists in the interwar years. In Britain such objects were approved by the state-funded Council of Industrial Design (see Design Council) and seen in opposition to the elaborate styling and obsolescence inherent in American design that was becoming attractive to British consumers, whilst in the United States, at theMuseum of Modern Art in New York, they were also seen as exemplars of European restraint.

A key text that has played an important role in defining Modernism has been Nikolaus Pevsner's widely read book, first published as Pioneers of the Modern Movement (1936). It has subsequently undergone substantial revisions (including a major one supported by the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1949) and numerous reprints under the title of Pioneers of Modern Design: From William Morris to Walter Gropius. Pevsner provides an account of the ways in which John Ruskin, William Morris, and exponents of the Arts and Crafts Movement fought against what they saw as the morally decadent and materialistic indulgence in historical ornamentation, inappropriate use of materials, and ‘dishonest’ modes of construction widely prevalent in Victorian design. This period was seen as a prelude to the clean, abstract, machine-made forms of 20th-century Modernism seen in the work of members of the Deutscher Werkbund and the teachers and students at the Bauhaus. Unlike the stylistic historicism of Victorian design, Modernism was felt to reflect the Zeitgeist. Its first phase emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries when arts and crafts principles of ‘honesty of construction’, ‘truth to materials’, and rejection of historical encyclopaedism were reconciled with the mass-production potential of the machine and blended with the embrace of new materials, technologies, and abstract forms. Important in such considerations, the main thrust of which moved from Britain to Germany, aided by the writings and outlook of Hermann Muthesius. He had worked as architectural attaché to the German Embassy in London in 1896, gaining a first-hand knowledge of progressive design thinking in Britain at the time. After returning to Germany in 1903, he was given major responsibilities for art and design education and influenced the appointment to key institutional posts of major figures such as Peter Behrens before taking up the Chair of Applied Arts at Berlin Commercial University in 1907. Muthesius was also a key figure in the establishment of the Deutscher Werkbund (DWB), founded in Munich in 1907 with the aim of improving the quality and design of German consumer products. There were considerable differences of opinion between those such as Henry van de Velde who believed in the primacy of individual artistic expression and supporters of Muthesius who favoured the use of standardized forms allied to quality production as a means of achieving economic success. The DWB and its celebrated large-scale exhibition in Cologne in 1914 attracted the attention of designers throughout Europe including members of the Swedish Society of Industrial Design and some of those associated with the foundation of the Design and Industries Association in Britain in 1915. Another important German exemplar of the exploration of new materials and abstract forms in its modernizing products, buildings, interiors, and corporate identity in the years leading up to the First World War was the large electricity generating and manufacturing company, AEG, whose design policy was coordinated by Peter Behrens.

Despite the massive disruption of the First World War certain aspects of avant-garde activity continued during the 1914-18 period, most notably the work of the De Stijl group in Holland, founded by Theo Van Doesburg in 1917. In Germany many of the progressive ideas at the core of Modernism were developed at the German Bauhaus, founded in Weimar in 1919 under the directorship of Walter Gropius. This radical and influential institution brought together art, craft, and design, allied to architecture, and was influenced strongly in the early 1920s by the ideas of De Stijl and Russian Constructivism. Many of those associated with it were major defining figures of Modernism including Marcel Breuer, Herbert Bayer, Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe, László Moholy-Nagy, Wilhelm Wagenfeld, Anni and Josef Albers, Marianne Brandt, and Gunta Stölzl. By the mid-1920s the DWB began to reassert an influence on contemporary design debates, whether through exhibitions such as Form ohne Ornament (Form without Ornament) in 1924 or the recommencement of publication of its propagandist magazine Die Forme. Modernism in Germany was also taken up in the mid-1920s by municipal authorities such as that in Frankfurt that instituted a large-scale housing programme under the City Architect Ernst May, developed ergonomic kitchen designs under Greta Schütte-Lihotsky, and promoted many aspects of a Modernist lifestyle in its magazine Das Neue Frankfurt. Similar developments could be found in many other European cities such as Rotterdam in Holland and Warsaw in Poland, as well as the large-scale Die Wohnung (The Dwelling) exhibition organized by the DWB in Stuttgart in 1927 where a number of buildings by leading Modernists were shown. These included designs by Le Corbusier from France, Mart Stam, and J. J. P. Oud from Holland, and Gropius and Mies Van Der Rohe from Germany and Victor Bourgeois from Belgium, all of which contained furniture and fittings that were characterized by a lightweight Modernist aesthetic very different from the heavy, often intrusive forms of traditional furniture. This collective manifestation reflected the increasingly international orientation of the movement, a dimension that attracted increasing antagonism on the part of conservative manufacturers, designers, architects, and critics who saw the style as un-Germanic and portrayed its designers and manufacturers as Bolsheviks, Jews, and other foreigners. In France, the Modernist cause had been effectively prosecuted by Le Corbusier, sustained by his theoretical writings such as Vers une architecture (1923) and L'Art decoratifs d'aujourd'hui (1925) and promoted in full public view in his uncompromising Pavillon de L'Esprit Nouveau at the Paris Exposition des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels of 1925. His stand against the prevailing decorative ethos of the luxurious pavilions elsewhere on the site was followed through in the establishment of the Union des Artistes Modernes (UAM) in 1929. This was the same year in which another important organization that furthered the international impact of Modernism was founded: the Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne (CIAM). In Sweden the Modernist debate was very much to the fore at the Stockholm Exhibition of 1930, following which a more humanizing dimension was seen with the emergence of what became known as Swedish Modern with its partiality for natural materials seen in the work of Bruno Mathsson and Josef Frank and articles promoted, manufactured, and sold by Svenskt Tenn in Stockholm. Other Scandinavian examples may be seen in the work of Alvar and Aino Aalto in Finland or Kaare Klint in Denmark. Modernism was also evident in both the graphic and rug design work of Edward McKnight Kauffer that was characterized by the interplay of flat, geometric forms similar to those explored by Marion Dorn, SergeChermayeff and drawing on the pioneering work of Gunta Stölzl, Anni Albers, and others at the Dessau Bauhaus in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

There were also several ways in which aspects of Modernism could be seen in certain outputs of the later phases of Art Deco, such as the use of flat, abstract shapes, geometrically conceived forms and modern materials in much American design work of the later 1920s and 1930s including some of the furniture of Paul Frankl, Donald Deskey, and Gilbert Rohde. American Streamlining also exhibited a number of modernizing tendencies, also blending new materials with clean, often organically inspired, forms that also drew on abstract decorative motifs symbolizing speed. In fact many dimensions of Modernist design endured throughout the rest of the 20th century, whether manifest in Charles Jencks's notions of Late Modernism or even incorporation as playful or ironic quotation in Postmodernism.

Fresh,new,contemporary.

Modernism-Modernism, also known as the Modern Movement, marked a conscious break with the past and has been one of the dominant expressions of design practice, production, and theory in the 20th century and is generally characterized visually by the use of modern materials such as tubular steel and glass, the manipulation of abstract forms, space and light, and a restrained palette, dominated by white, off-white, grey, and black. Following on from the well-known phrase ‘Ornament and Crime’ coined by Adolf Loos as the title of an article of 1908, later echoed by Le Corbusier in his assertion that ‘trash is always abundantly decorated’, was the notion that the surfaces were generally plain. When decoration was used it was restrained and attuned to the abstract aesthetic principles of the artistic avant-garde such as those associated with De Stijl orConstructivism. Also closely associated with Modernism was the maxim ‘form follows function’ although in reality this was often more symbolic than the case in reality, a visual metaphor for the Zeitgeist or spirit of the age. Nonetheless Modernism found forms of material expression alongside exciting, new, and rapidly evolving forms of transport and communication, fresh modes of production and materials coupled to technological and scientific change, alongside a contemporary lifestyle powered by electricity.

The roots of Modernism lie in the design reform movement of the 19th century and were nurtured in Germany in the years leading up to the First World War. The Modernist legacy is considerable in terms of design (whether furniture, tableware, textiles, lighting, advertising, and typography or other everyday things), architecture (whether public or private housing, cinemas, office blocks, and corporate headquarters), or writings (theories, manifestos, books, periodicals, and criticism). This has done much to cement Modernism firmly into the mainstream history of design. Furthermore, it is also heavily represented in numerous museums around the world that have centred their design collections drawn from the later 19th century through to the last quarter of the 20th century around the Modernist aesthetic and its immediate antecedents. This focused collecting policy has generally been at the expense of the representation of many other aspects of design consumed by the majority in the same period. Typifying such an outlook has been the Museum of Modern Art in New York, established in 1929. The curatorial inclinations of Philip Johnson, Eliot Noyes, and Edgar Kaufmann Jr. dominated its collecting policy for several decades. A further significant reason for the prominence of Modernism in accounts of design in the 1920s and, more particularly, the 1930s has been the fact that it was underpinned by social utopian ideals and identified with radical avant-garde tendencies opposed to the repressive political and aesthetic agendas of totalitarian regimes that dominated in Germany, Russia, and Italy. In general, official architecture and design practice under Adolf Hitler and Josef Stalin favoured an authoritarian, stripped down neoclassical style, leading many progressive designers in Germany in particular to emigrate in the face of restricted professional opportunities and increasing political and social oppression. In dictator Benito Mussolini's Fascist Italy, the position was slightly more ambivalent during the 1920s but the Modernist aspirations of those associated with Italian Rationalism found little official patronage in the interwar years. To many eyes in 1930s Britain Modernism was also felt to reflect ‘Bolshevik’ tendencies and was out of tune with the more historically inclined stylistic rhetoric of British imperialism (see British Empire Exhibition), an outlook that oriented Britain away from continental Europe towards the dominions and colonies of Empire. Known also as the International Style from the late 1920s onwards, a later phase of Modernism was also, by its very definition and aspiration, opposed to the strongly nationalistic tendencies in many countries in the turbulent political and economic climate of the 1930s. Less affected by the political turmoil in the rest of Europe were Holland and Scandinavia where Modernism found considerable opportunities for further development and dissemination. After the Second World War the International Style was taken up by many major multinational companies for the architecture, interiors, furniture, and furnishings and equipment of their offices and showrooms, thus promoting themselves through their emphatically modern identity as efficient, up-to-date, and internationally significant organizations in a global economy. In the eyes of some, Modernism's earlier associations with social democratic ideals had been transmuted in its later manifestations to support capitalist ends. Used widely in design and architecture in the 1950s and 1960s, such stylistic traits also attracted increasing criticism from a younger generation of designers, architects, and critics who felt that an abstract design vocabulary that had evolved in the early decades of the 20th century was no longer relevant in an era of rapid and dynamic change, of television and radically developing media and communication systems, and of swiftly developing opportunities for mass travel and the direct experience of other cultures. Such trends found expression in the increasingly rich and vibrant vocabulary of Postmodernism, echoed in the increasingly ephemeral lifestyle enjoyed by those in the industrial world with greater levels of disposable income. Ideas about what was called ‘Good Design’ in the 1950s and 1960s were formally linked to the Modernist aesthetic but without the social utopian underpinning promoted by many of the first generation of Modernists in the interwar years. In Britain such objects were approved by the state-funded Council of Industrial Design (see Design Council) and seen in opposition to the elaborate styling and obsolescence inherent in American design that was becoming attractive to British consumers, whilst in the United States, at theMuseum of Modern Art in New York, they were also seen as exemplars of European restraint.

A key text that has played an important role in defining Modernism has been Nikolaus Pevsner's widely read book, first published as Pioneers of the Modern Movement (1936). It has subsequently undergone substantial revisions (including a major one supported by the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1949) and numerous reprints under the title of Pioneers of Modern Design: From William Morris to Walter Gropius. Pevsner provides an account of the ways in which John Ruskin, William Morris, and exponents of the Arts and Crafts Movement fought against what they saw as the morally decadent and materialistic indulgence in historical ornamentation, inappropriate use of materials, and ‘dishonest’ modes of construction widely prevalent in Victorian design. This period was seen as a prelude to the clean, abstract, machine-made forms of 20th-century Modernism seen in the work of members of the Deutscher Werkbund and the teachers and students at the Bauhaus. Unlike the stylistic historicism of Victorian design, Modernism was felt to reflect the Zeitgeist. Its first phase emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries when arts and crafts principles of ‘honesty of construction’, ‘truth to materials’, and rejection of historical encyclopaedism were reconciled with the mass-production potential of the machine and blended with the embrace of new materials, technologies, and abstract forms. Important in such considerations, the main thrust of which moved from Britain to Germany, aided by the writings and outlook of Hermann Muthesius. He had worked as architectural attaché to the German Embassy in London in 1896, gaining a first-hand knowledge of progressive design thinking in Britain at the time. After returning to Germany in 1903, he was given major responsibilities for art and design education and influenced the appointment to key institutional posts of major figures such as Peter Behrens before taking up the Chair of Applied Arts at Berlin Commercial University in 1907. Muthesius was also a key figure in the establishment of the Deutscher Werkbund (DWB), founded in Munich in 1907 with the aim of improving the quality and design of German consumer products. There were considerable differences of opinion between those such as Henry van de Velde who believed in the primacy of individual artistic expression and supporters of Muthesius who favoured the use of standardized forms allied to quality production as a means of achieving economic success. The DWB and its celebrated large-scale exhibition in Cologne in 1914 attracted the attention of designers throughout Europe including members of the Swedish Society of Industrial Design and some of those associated with the foundation of the Design and Industries Association in Britain in 1915. Another important German exemplar of the exploration of new materials and abstract forms in its modernizing products, buildings, interiors, and corporate identity in the years leading up to the First World War was the large electricity generating and manufacturing company, AEG, whose design policy was coordinated by Peter Behrens.

Despite the massive disruption of the First World War certain aspects of avant-garde activity continued during the 1914-18 period, most notably the work of the De Stijl group in Holland, founded by Theo Van Doesburg in 1917. In Germany many of the progressive ideas at the core of Modernism were developed at the German Bauhaus, founded in Weimar in 1919 under the directorship of Walter Gropius. This radical and influential institution brought together art, craft, and design, allied to architecture, and was influenced strongly in the early 1920s by the ideas of De Stijl and Russian Constructivism. Many of those associated with it were major defining figures of Modernism including Marcel Breuer, Herbert Bayer, Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe, László Moholy-Nagy, Wilhelm Wagenfeld, Anni and Josef Albers, Marianne Brandt, and Gunta Stölzl. By the mid-1920s the DWB began to reassert an influence on contemporary design debates, whether through exhibitions such as Form ohne Ornament (Form without Ornament) in 1924 or the recommencement of publication of its propagandist magazine Die Forme. Modernism in Germany was also taken up in the mid-1920s by municipal authorities such as that in Frankfurt that instituted a large-scale housing programme under the City Architect Ernst May, developed ergonomic kitchen designs under Greta Schütte-Lihotsky, and promoted many aspects of a Modernist lifestyle in its magazine Das Neue Frankfurt. Similar developments could be found in many other European cities such as Rotterdam in Holland and Warsaw in Poland, as well as the large-scale Die Wohnung (The Dwelling) exhibition organized by the DWB in Stuttgart in 1927 where a number of buildings by leading Modernists were shown. These included designs by Le Corbusier from France, Mart Stam, and J. J. P. Oud from Holland, and Gropius and Mies Van Der Rohe from Germany and Victor Bourgeois from Belgium, all of which contained furniture and fittings that were characterized by a lightweight Modernist aesthetic very different from the heavy, often intrusive forms of traditional furniture. This collective manifestation reflected the increasingly international orientation of the movement, a dimension that attracted increasing antagonism on the part of conservative manufacturers, designers, architects, and critics who saw the style as un-Germanic and portrayed its designers and manufacturers as Bolsheviks, Jews, and other foreigners. In France, the Modernist cause had been effectively prosecuted by Le Corbusier, sustained by his theoretical writings such as Vers une architecture (1923) and L'Art decoratifs d'aujourd'hui (1925) and promoted in full public view in his uncompromising Pavillon de L'Esprit Nouveau at the Paris Exposition des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels of 1925. His stand against the prevailing decorative ethos of the luxurious pavilions elsewhere on the site was followed through in the establishment of the Union des Artistes Modernes (UAM) in 1929. This was the same year in which another important organization that furthered the international impact of Modernism was founded: the Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne (CIAM). In Sweden the Modernist debate was very much to the fore at the Stockholm Exhibition of 1930, following which a more humanizing dimension was seen with the emergence of what became known as Swedish Modern with its partiality for natural materials seen in the work of Bruno Mathsson and Josef Frank and articles promoted, manufactured, and sold by Svenskt Tenn in Stockholm. Other Scandinavian examples may be seen in the work of Alvar and Aino Aalto in Finland or Kaare Klint in Denmark. Modernism was also evident in both the graphic and rug design work of Edward McKnight Kauffer that was characterized by the interplay of flat, geometric forms similar to those explored by Marion Dorn, SergeChermayeff and drawing on the pioneering work of Gunta Stölzl, Anni Albers, and others at the Dessau Bauhaus in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

There were also several ways in which aspects of Modernism could be seen in certain outputs of the later phases of Art Deco, such as the use of flat, abstract shapes, geometrically conceived forms and modern materials in much American design work of the later 1920s and 1930s including some of the furniture of Paul Frankl, Donald Deskey, and Gilbert Rohde. American Streamlining also exhibited a number of modernizing tendencies, also blending new materials with clean, often organically inspired, forms that also drew on abstract decorative motifs symbolizing speed. In fact many dimensions of Modernist design endured throughout the rest of the 20th century, whether manifest in Charles Jencks's notions of Late Modernism or even incorporation as playful or ironic quotation in Postmodernism.

Tuesday, 30 November 2010

Graphic Design A Media For The Masses, Notes

- Bison And Horses 15000 - 10000 bc

- Everything is a form of communication

- John Everett millais, Bubbles.

- 1922 William addison Dwiggins.

- Definition of Design

- Herbert Spencer - Mechanized art.

- Steven Heller 1995 - Graphic Designers are trying to prove that they are not a result of capitalism.

- Doing good for society instead of selling sit.

- Art Deco..Alphonse mucha 1899

- The early stages of GD was a mixture of disciplines between art and design.

- Peter Behrens

- Julius Gipkons

- El Liisitsky - Beat the whites

- F.H - Stingemore - London Underground.

- Oscar Sclhemmar - created the Bauhaus Logo.

- Herbert Matter - swatch

- A.M. cassandre

- Hans Schleger - eat greens

- Franz Ferdinand

- Peter Catala-Lets Squash Fascism

- GD or Advertising

- Think Small Campaign

- Paul Rand IBM

- Capitalist Culture

- More to life than promoting the buying and selling of products.

- Economic referances for design

- Art workers coalition and babies

- Post Punk - Peter Saville ( new order)

- Neville Broads

- Is it graphic design for the sake of being graphic design?

- If its an object of beauty? does it then become art?

- Picture of starving children - Chumbawumba

- The Coup-Part music. Controversial album cover?

- Oliviero toscani - Benetton Ad.

- Ad Busters.

5 examples of Modernist GD

By Nekrayen and Luppili. Lenin's Young Guard,1920 and poster c1920-23 shows Lenin and Trotsky. Taken from www.tonyscanlonposters.com/russian.php?photo=453.

The reason behind me choosing this poster to represent modernist graphic design, is for two main reasons, the use of the san serifed type face and the photomontage that forms the basis of the Russian revolutionary poster.

By Walter Allner. This was one of a collection of 79 covers for Fortune magazine. Where he was art director from 1962-1974. The reason i chose this piece to represent modernism is because of the use of synthetic colours and the style of print. which shows a progressing from the earliest form of print to modern day. taken from http://30gms.com/tags/C27/P40/

This is an insurances poster created in france, during the first world war 1914. by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. the reason for me choosing this piece is because of the time it was created soon after the industrial revolution in france. And it is an early example of type being manipulated in size and style on the piece of work, which suggest modernism.

This is a poster created at the bauhaus by Herbert Bayer, in 1926, for kandinsky's 6o th birthday exhibition. The reason for choosing this again, is based around the san serifed type face, which was created at the Bauhaus establishment. Its is a very clean image, but is representative of the style of kandinsky himself, by using type manipulation again. Something that is representative of modernist design.

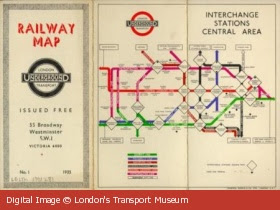

This is an example of Harry Beck's london Underground map, created in 1933.That is so noticeable today. It is a prime example of modernist design. He was one of the first British designers to move away from a fine Art influence. With a definite purpose of instruction on mind. It is a very structured example of modernist design. With again letter manipulation different styles with in words. And it is for this reason i have chosen it.

Monday, 8 November 2010

Lecture Modernism And Modernity.

MODERNITY AND MODERNISM LECTURE.

· Urbanisation- the city

· Modern perceived as ‘not cool’ by traditionalist of the 18th century. However pre Raphaelites changed that, and progression became accepted.

· Holman hunt (1851) .

· Are we post modern?

· Paris in the 1900 was the most modern city in the world.

· Urbanisation creates a change in life and life styles in the city, much more accessible.

· Enlightenment period in the 18th cent when science and philosophical thinking cam on leaps and bounds.

· Secularisation

· Paris on a rainy day 1877, painting the new Paris.

· Re designed Paris, large boulevards, based around transport routes, socially desirable city.

· Alienation part of modernity?

· Psychology becomes relevant perhaps due to alienation people going mad etc.

· An increasing class divide.

· Kaiser panorama 1883

· Technology-cinema.

· Modernism is the artist and designers responses to the changing world. (modern)

· Painting had to change with the invention of photography.

· Alfred Stieglitz 1903

· Paul Citroen 1903

· Photo montage becomes relevant

· George Grosz

MODERNISM IN DESIGN

· Anti historicism – no need to look backwards

· Truth to materials – material of the modern world.

· Form Follows function

· Internationalism a modern design should speak a common language.

· Ornament is crime- Adolf Loos.

· Truth to the materials-simple geometric forms appropriate to the material used.

· Bauhaus

· Modern design-new materials

· Mass production

· …building new york.

· Le Corbusier ideal city 1922

· Internationlism the language of desing which is global.

· Harry Beck London underground 1935

· San Serifed font.

· While people were designing hyper modern fonts, people started to look backwards and edit old serifed fonts, i.e. x new roman..

· Frakter- Nazi

· Modernity- social and cultural experience.

· Novelty and improvement

· Modernism a range of ideas and style sprung from modernity. Art and design, vocab, form follows function.

Essay Compare and Contrast Savile Lumley And Schumacher and Ettinger.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST THE TWO IMAGES IN RELATION TO THE FOLLOWIG:

A/The choice and organisation of font and style of illustration.

B/The purpose and meaning of the image

C/The target/potential audience of the image

D/The social and historical contexts relevant to the production of the image.

The two images shown differ greatly in subject matter. The Great War image is a propaganda poster from ww1, encouraging people to sign up for the war effort. Where as the Uncle Sam image is an advertisement is for a range of cookers, one hundred years on from the American war of independence.

The Uncle Sam advertisement through out has a very nationalistic, garish approach in design, with the use of the American colours red, white and blue through out,. The stars and stripes are also apparent in the image, what this portrays is a very patriotic and gives the advert the identity of America, at the time the world super power, as a result demonstrating prosperity. This is also shown in the type used, when looking at the type used you are immediately drawn to the bold Uncle Sam Range. The typeface used here is commonly thought of to be associated with America especially in the ‘wild west’. Which is another example of the nationalistic standpoint the creators of the range are trying to show and force into the audiences mind. Uncle Sam himself being at the centre of the image is a clear indication that to buy this cooker would be buying into the lifestyle of the American dream.

The clock above the fireplace highlights another subject matter running through the piece, that of celebration of having independence. The clock shows the one hundred years that has passed since independence.1776-1876. The celebratory dinner party that is occurring in the image also shows this. Centenary hall is portrayed in the image, which was built for the one hundred year celebration and is another example of prosperity and power.

Finally with in the image there is a theme of American superiority, the menu at the centre of the image demonstrates this. As it is trying to portray that other counties have not become civilized in what they consume, as they are focusing on stereotypes (. i.e. Irish and potatoes) unlike the Americans. In the modern day this is perceived as a racist point of view.

The second image in contrast was created at the time of the Great War. A war with huge significance to the way in which the world developed. This image is based around the feeling of guilt and worthlessness if you were not to enrol into the war effort. These feelings are immediately highlighted by the texted used, with the underlining of the word you. Asking specifically what you yourself have done to help the country in its time of need? The italic almost cute typeface is meant to represent the daughter’s voice that is sitting on her father’s knee. This plays on the emotion of wanting to be the right kind of teacher to your children, and by not going to war are you doing this?

The persuasiveness that is a theme throughout the two images, however they are both demonstrated in different manners, one being war propaganda the other playing on patriotism to purchase a cooker. There is however some patriotism and national identity in the war poster with the red rose of England as the pattern of the curtain and the fleur-de-lis on the chair which is a clear indication of British royalty. National identity and royalty is also demonstrated by the boy playing with queen’s toy soldiers, again playing on the idea of guilt.

On initial viewing the images appear greatly diverse in style and meaning, there are common themes of national identity and persuasiveness.

Wednesday, 20 October 2010

Visual language.

Verb-doing word.

Adverb-describing the doing word.

Noun-object/person.

Pro Noun-he/she/which/us/you/me.

Subjective Personal Pronoun-he/she/i/me

Adjective-descriibng word.

Newspaper Articles.

X factors Wagner moves out of Hertfordshire home. After John Adeleyes liberal spraying of deodorant angers him. He will only return to the house for vocal training.

Fergy refuses to answer questions on Wayne Rooney's future. After he allegedly refused to sign a new contract. He has been linked with the likes of Chelsea,City and Madrid.

Letters.

Balance/Shatter.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)